Derek W. Black ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

University of South Carolina apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation US.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

Public school funding has shrunk over the past decade. School discipline rates reached historic highs. Large achievement gaps persist. And the overall performance of our nation’s students falls well below our international peers.

These bleak numbers beg the question: Don’t students have a constitutional right to something better? Many Americans assume that federal law protects the right to education. Why wouldn’t it? All 50 state constitutions provide for education. The same is true in 170 other countries. Yet, the word “education” does not appear in the United States Constitution, and federal courts have rejected the idea that education is important enough that it should be protected anyway.

After two decades of failed lawsuits in the 1970s and ‘80s, advocates all but gave up on the federal courts. It seemed the only solution was to amend the Constitution itself. But that, of course, is no small undertaking. So in recent decades, the debate over the right to education has mostly been academic.

The summer of 2016 marked a surprising turning point. Two independent groups – Public Counsel and Students Matter – filed lawsuits in Michigan and Connecticut. They argue that federal law requires those states to provide better educational opportunities for students. In May 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a similar suit in Mississippi.

At first glance, the cases looked like long shots. However, my research shows that these lawsuits, particularly in Mississippi, may be onto something remarkable. I found that the events leading up to the 14th Amendment – which explicitly created rights of citizenship, equal protection and due process – reveal an intent to make education a guarantee of citizenship. Without extending education to former slaves and poor whites, the nation could not become a true democracy.

Even today, a federal constitutional right to education remains necessary to ensure all children get a fair shot in life. While students have a state constitutional right to education, state courts have been ineffective in protecting those rights.

Without a federal check, education policy tends to reflect politics more than an effort to deliver quality education. In many instances, states have done more to cut taxes than to support needy students.

And a federal right is necessary to prevent random variances between states. For instance, New York spends US$18,100 per pupil, while Idaho spends $5,800. New York is wealthier than Idaho, and its costs are of course higher, but New York still spends a larger percentage on education than Idaho. In other words, geography and wealth are important factors in school funding, but so is the effort a state is willing to make to support education.

And many states are exerting less and less effort. Recent data show that 31 states spend less on education now than before the recession – as much as 23 percent less.

States often makes things worse by dividing their funds unequally among school districts. In Pennsylvania, the poorest districts have 33 percent less per pupil than wealthy districts. Half of the states follow a similar, although less extreme, pattern.

Studies indicate these inequities deprive students of the basic resources they need, particularly quality teachers. Reviewing decades of data, a 2014 study found that a 20 percent increase in school funding, when maintained, results in low-income students completing nearly a year of additional education. This additional education wipes out the graduation gap between low- and middle-income students. A Kansas legislative study showed that “a 1 percent increase in student performance was associated with a .83 percent increase in spending.”

These findings are just detailed examples of the scholarly consensus: Money matters for educational outcomes.

While normally the refuge for civil rights claims, federal courts have refused to address these educational inequalities. In 1973, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected education as a fundamental right. Later cases asked the court to recognize some narrower right in education, but the court again refused.

After a long hiatus, new lawsuits are now offering new theories in federal court. In Michigan, plaintiffs argue that if schools do not ensure students’ literacy, students will be consigned to a permanent underclass. In Connecticut, plaintiffs emphasize that a right to a “minimally adequate education” is strongly suggested in the Supreme Court’s past decisions. In Mississippi, plaintiffs argue that Congress required Mississippi to guarantee education as a condition of its readmission to the Union after the Civil War.

While none of the lawsuits explicitly state it, all three hinge on the notion that education is a basic right of citizenship in a democratic society. Convincing a court, however, requires more than general appeals to the value of education in a democratic society. It requires hard evidence. Key parts of that evidence can be found in the history of the 14th Amendment itself.

Immediately after the Civil War, Congress needed to transform the slave-holding South into a working democracy and ensure that both freedmen and poor whites could fully participate in it. High illiteracy rates posed a serious barrier. This led Congress to demand that all states guarantee a right to education.

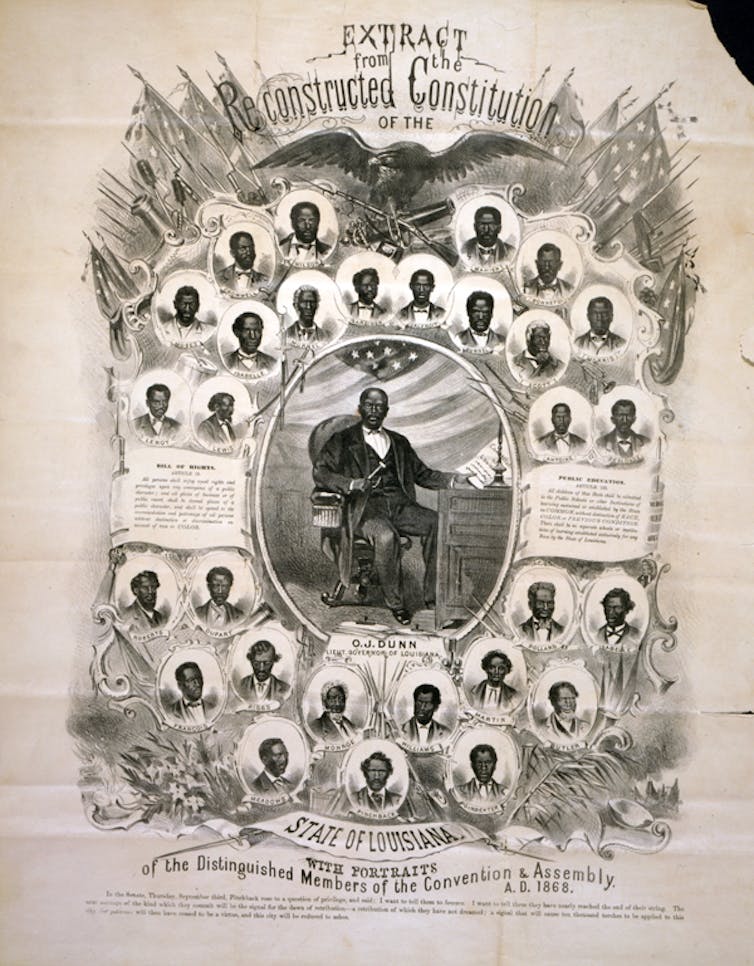

In 1868, two of our nation’s most significant events were occurring: the readmission of southern states to the Union and the ratification of the 14th Amendment. While numerous scholars have examined this history, few, if any, have closely examined the role of public education. The most startling thing is how much persuasive evidence is in plain view. Scholars just haven’t asked the right questions: Did Congress demand that southern states provide public education, and, if so, did that have any effect on the rights guaranteed by the 14th Amendment? The answers are yes.

As I describe in the Constitutional Compromise to Guarantee Education, Congress placed two major conditions on southern states’ readmission to the Union: Southern states had to adopt the 14th Amendment and rewrite their state constitutions to conform to a republican form of government. In rewriting their constitutions, Congress expected states to guarantee education. Anything short was unacceptable.

Southern states got the message. By 1868, nine of 10 southern states seeking admission had guaranteed education in their constitutions. Those that were slow or reluctant were the last to be readmitted.

The last three states – Virginia, Mississippi and Texas – saw Congress explicitly condition their readmission on providing education.

The intersection of southern readmissions, rewriting state constitutions and the ratification of the 14th Amendment helps to define the meaning of the 14th Amendment itself. By the time the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, state constitutional law and congressional demands had cemented education as a central pillar of citizenship. In other words, for those who passed the 14th Amendment, the explicit right of citizenship in the 14th Amendment included an implicit right to education.

The rest is history. Our country went from one in which fewer than half of states guaranteed education prior to the war to one in which all 50 state constitutions guarantee education today.

The new cases before the federal courts offer an opportunity to finish the work first started during Reconstruction – to ensure that all citizens receive an education that equips them to participate in democracy. The nation has made important progress toward that goal, but I would argue so much more work remains. The time is now for federal courts to finally confirm that the United States Constitution does, in fact, guarantee students the right to quality education.